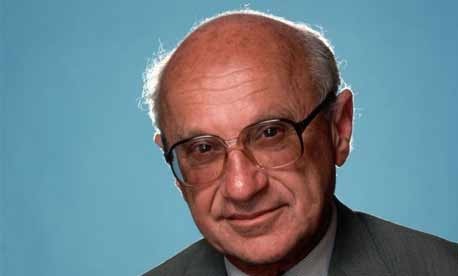

Free Market Advocates Mark Milton Friedman's 100th Birthday

Underneath the conspicuous partisan quarreling between Republicans and Democrats in the United States today, there is another more substantive debate happening-- one that involves numbers, graphs, research, history, and some very nuanced thinking about human behavior-- a debate that strikes to the very core of many major public policy issues Americans face: and that is the debate between the Keynesian economic theory that has dominated our understanding of public policy and its effects for the last century, and its various competing theories, including the Austrian school of economic thought made famous by Congressman Ron Paul and the Chicago school of economics advanced by Milton Friedman during his tenure at the University of Chicago.

Born on July 31, 1912, today would have been Professor Milton Friedman's 100th birthday (Friedman died in 2006) and his friends, colleagues, and fellow free market proponents marked the centennial with glowing words of praise for the 1976 Nobel Prize Laureate for Economic Science. At Real Clear Politics, Thomas Sowell wrote:

"Most people would not be able to understand the complex economic analysis that won him a Nobel Prize, but people with no knowledge of economics had no trouble understanding his popular books like 'Free to Choose' or the TV series of the same name.In being able to express himself at both the highest level of his profession and also at a level that the average person could readily understand, Milton Friedman was like the economist whose theories and persona were most different from his own -- John Maynard Keynes."

Enjoying a recent Keynesian Resurgence during the global economic crisis beginning at the end of the Bush Administration, the economic theory of influential British economist John Maynard Keynes is a theory of:

"...total spending in the economy (called aggregate demand) and its effects on output and inflation...A Keynesian believes that aggregate demand is influenced by a host of economic decisions—both public and private—and sometimes behaves erratically. The public decisions include, most prominently, those on monetary and fiscal (i.e., spending and tax) policies."

But, as the Wall Street Journal's Monday retrospective on Milton Friedman's work explains, the University of Chicago economist challenged the orthodoxy of the Keynesian model, arguing that the manipulation of macroeconomic phenomena by technocratic central planners would inevitably result in less desirable economic outcomes by mis-allocating productive financial resources to less productive uses than the free operation of the marketplace would:

"In the 1960s, Friedman famously explained that 'there's no such thing as a free lunch.' If the government spends a dollar, that dollar has to come from producers and workers in the private economy. There is no magical 'multiplier effect' by taking from productive Peter and giving to unproductive Paul...Equally illogical is the superstition that government can create prosperity by having Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke print more dollars. In the very short term, Friedman proved, excess money fools people with an illusion of prosperity. But the market quickly catches on, and there is no boost in output, just higher prices."

Instead, Friedman's solution is the competition of businesses in a free market. Rather than a limited number of technocrats with limited knowledge making some of these macroeconomic decisions, Friedman's solution is to allow the price system of the marketplace to elegantly coordinate the disparate knowledge of millions of market actors to appraise the value of competing opportunities and goods so that market actors can spend their money on those likely to yield the greatest return in either production or utility.

Whether Friedman's theory, that of John Maynard Keynes, another competing economic school, or some mix of them all is correct, these are substantive, empirically-driven public policy discussions worth having, and discerning some of the right answers could make a world of difference in the lives of millions or even billions of people. Independents can lead the way on an earnest, academic assessment of the economic policy debate and leave bitter, partisan, "fighting words" at the door.