How Do Primary Elections Work? An Overview and Legal Analysis

The following is a breakdown of the general types of primary elections with an explanation of the Constitutional principles that apply to each system's components.

Primary Systems – General Background

Prior to legal analysis of primary election laws, it is imperative that we have a strong understanding of definitions used to refer to each type and component of a primary election. Often times, public discussion has misused or misplaced terminology that can lead to confusion even among those well versed in primary election law. It is essential that we clearly define these particular terms in light of the Constitutional considerations that arise from each.

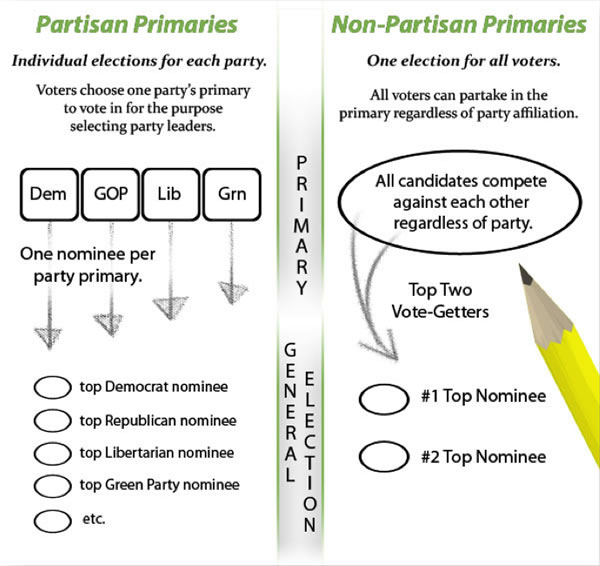

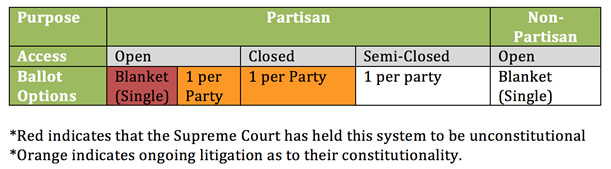

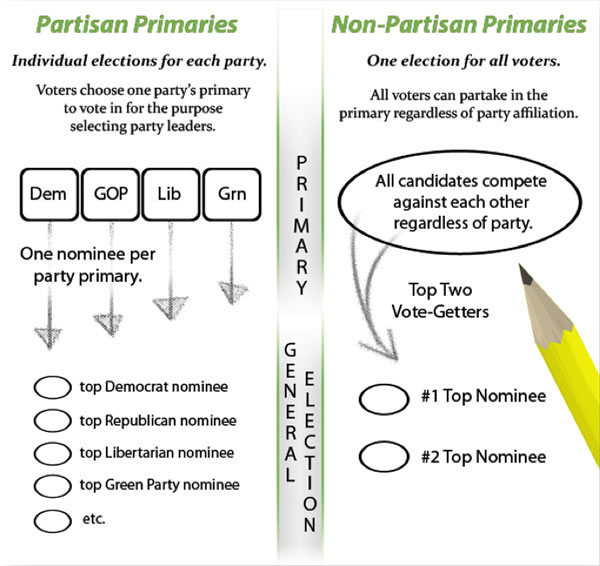

For example, the term “open” refers to the access, herein defined, that a voter has to vote for the candidate(s) of his or her choice. But “open” is not a complete term. An “open primary” can be conducted for a partisan purpose, or a nonpartisan purpose. A “partisan open primary” can be conducted using a single ballot (AKA “blanket open primary”), or a separate ballot for each party, whereas a “non-partisan primary” may only be conducted on a single ballot.

Therefore, to provide a complete term, a primary’s description should include at least the following components:

Purpose

The purpose of a primary is the most important, yet often overlooked factor in the construct of a primary election. The purpose of a primary election is defined by one of two fundamental characteristics: (1) Partisan, or (2) Non-partisan.

“When we interpret the meaning of statutes, our fundamental task is to ascertain the aim and goal of the lawmakers so as to effectuate the purpose of the statute.” (McAllister v. California Coastal Com. (2008) 169 Cal.App.4th 912, 928, 87 Cal.Rptr.3d 365.)

The following illustrates the difference between California’s old partisan primary and new “Top-Two” non-partisan primary systems.

(1) Partisan

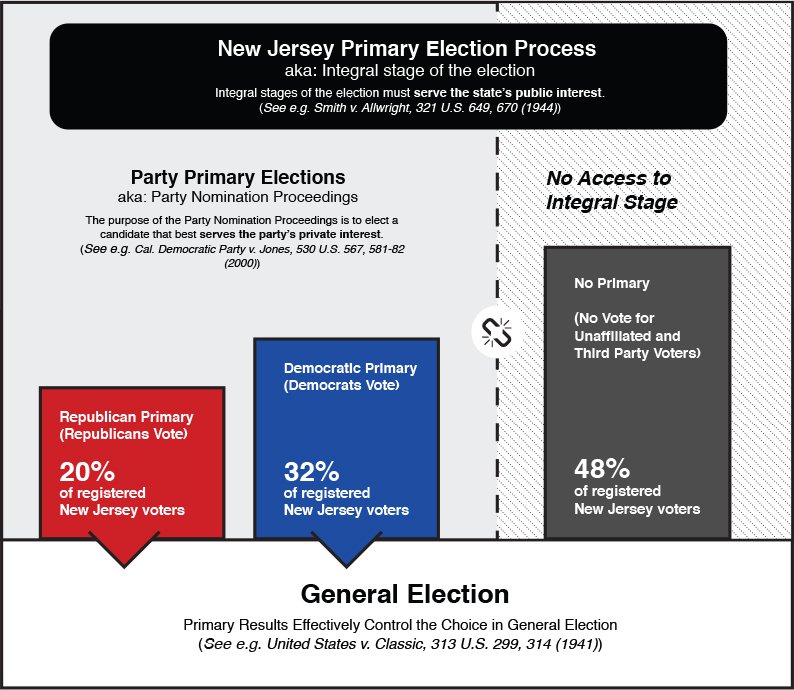

Partisan primaries come in many forms, depending on the access and ballot options (discussed below) a voter is afforded. A partisan primary election is best conceived as individual elections conducted at the same time for each qualified political party. Partisan primaries are practiced in 47 of 50 states. However, regardless of these peculiarities, partisan primaries always serve the same private purpose:

The purpose of a partisan primary is for members of political parties to nominate candidates for the general election and elect party officers. see e.g. California Democratic Party, 530 U.S. at 572-73.

Because partisan elections are conducted for a private purpose, a party’s private right of association always attaches.

Unsurprisingly, our cases vigorously affirm the special place the First Amendment reserves for, and the special protection it accords, the process by which a political party “select[s] a standard bearer who best represents the party's ideologies and preferences.” Eu, supra, at 224, 109 S.Ct. 1013 California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567, 575, 120 S. Ct. 2402, 2408, 147 L. Ed. 2d 502 (2000)

It is a state-granted right and must be balanced with an individual voter’s fundamental right to vote.

The rights of party members may to some extent offset the importance of claimed conflicting rights asserted by persons challenging some aspect of the candidate selection process. Nader v. Schaffer, 417 F. Supp. 837, 845 (D. Conn. 1976) aff'd, 429 U.S. 989, 97 S. Ct. 516, 50 L. Ed. 2d 602 (1976).

(2) Non-partisan

Non-partisan primaries serve a public purpose. Non-partisan primaries have a singular form with respect to the access and options an individual voter is afforded. A non-partisan primary is conducted as one election, where all voters and candidates participate in a single primary election using a single ballot. While non-partisan primaries can vary in form based on other particularities (such as “Top-Two” or “Top-Four”), for purposes of the legal considerations in this case, our inquiry will be limited to the general purpose.

Non-partisan primaries do not need to be qualified by the defining characteristics of access and options, because the access to all nonpartisan primaries is open and the ballots are necessarily a blanket style. In other words, voters must have the option to vote for any candidate, regardless of office or partisan considerations. Therefore, nonpartisan primaries are always Open, Blanket, and conducted for a nonpartisan public purpose:

The [Washington nonpartisan primary] law never refers to the candidates as nominees of any party, nor does it treat them as such. To the contrary, the election regulations specifically provide that the primary “does not serve to determine the nominees of a political party but serves to winnow the number of candidates to a final list of two for the general election.” Washington State Grange v. Washington State Republican Party, 552 U.S. 442, 453, 128 S. Ct. 1184, 1192, 170 L. Ed. 2d 151 (2008).

Access

Access refers to the ability of an individual voter to participate in the primary election process based on his or her party affiliation. There are three main definitions that comprise the access category: (1) Open, (2) Closed, and (3) Semi-Closed.

(1a) Open [Partisan]

The term open refers to the ability of a voter to choose a ballot of his or her choice. An “open partisan primary” can, itself, have a number of variations. However, for purposes of Constitutional analysis, we should consider the term “open,” to refer to any primary where a political party cannot prevent non-members from voting for their candidates.

The Courts have held that open partisan primaries violate a political party’s first amendment right of association.

In sum, [an open primary] forces petitioners to adulterate their candidate-selection process—the “basic function of a political party,” ibid.—by opening it up to persons wholly unaffiliated with the party. Such forced association has the likely outcome—indeed, in this case the intended outcome— of changing the parties' message. We can think of no heavier burden on a political party's associational freedom. California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567, 581-82, 120 S. Ct. 2402, 2412, 147 L. Ed. 2d 502 (2000).

(1b) Open [NonPartisan]

All nonpartisan primaries are necessarily open, see supra. While partisan open primaries have met ill fate in the Courtroom, open nonpartisan primaries have withstood Constitutional scrutiny. This is because nonpartisan schemes avoid the parties’ 1st Amendment concerns.

The Supreme Court stated that under such a system, ‘a State may ensure more choice, greater participation, increased privacy and sense of fairness – all without severely burdening a political party’s First Amendment right of association.” (dicta in Democratic Party v. Jones).

(2) Closed

The term closed refers to the inability of a voter to participate in the nomination of party candidates unless they are registered members of that party. The closed primary has been challenged in a few states based on the theory that a voter’s fundamental right to vote under the 14th amendment should not be conditioned on that voter giving up their 1st amendment right not to affiliate with a political party.

“Given the state's interest in protecting the associational rights of party members and in preserving the integrity of the electoral process, the state may legitimately allow political parties to close their primaries to nonmembers.” Ziskis v. Symington, 47 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 1995)

Courts have held that closed primaries are Constitutional, despite the fact that a voter’s participation in the primary is conditional. The fatal flaw in each case is the remedy requested: to open the primaries. This wouldn’t be such a fatal flaw if the Courts (and the Plaintiffs) didn’t assume that the primary system had to be a partisan one.

The comparative merits of various forms of primary election systems have been widely debated in this presidential election year. In particular, the “open” and “crossover” primaries, which permit independents and/or members of other parties to participate in a given party's primary, have been the subject of controversy. Nader v. Schaffer, 417 F. Supp. 837, 849 (D. Conn. 1976) aff'd, 429 U.S. 989, 97 S. Ct. 516, 50 L. Ed. 2d 602 (1976)

Note, in the opinion above, the court compares the “merits of various forms of primary election systems,” without considering the merits of a nonpartisan system. All references refer to systems designed for the purpose of selecting party nominees.

The rights of party members may to some extent offset the importance of claimed conflicting rights asserted by persons challenging some aspect of the candidate selection process. 525 F.2d at 588; see also Cousins v. Wigoda, supra, 419 U.S. at 487, 95 S.Ct. 541. More importantly, party members are entitled to affirmative protection of their associational rights, see Note, 27 Rutgers L.Rev. 298 (1974). Nader v. Schaffer, 417 F. Supp. 837, 845 (D. Conn. 1976) aff'd, 429 U.S. 989, 97 S. Ct. 516, 50 L. Ed. 2d 602 (1976)

Because open partisan primaries are themselves unconstitutional (see supra), a challenge to closed primaries would have a greater likelihood if the remedy requested was an open nonpartisan primary.

In evaluating the State’s interests, the Supreme Court noted that the First Amendment infringement [that results from the conflicting interests in a partisan primary] could be avoided by “resorting to a nonpartisan blanket primary… (dicta in Democratic Party v. Jones).

(3) Semi-Closed

Semi-closed refers to a partisan primary system in which a political party has the option, but not obligation, to allow or disallow non-members to participate. In California, for example, the election for all offices are conducted as nonpartisan “top-two” primaries, except for the office of President, which is held as a semi-closed primary.

Semi-closed primaries have withstood Constitutional muster, despite the fact that an individual voter’s rights are conditioned on a party allowing him or her to participate.

The First Amendment reserves a special place, and accords a special protection, for that process, Eu, supra, at 224, 109 S.Ct. 1013, because the moment of choosing the party's nominee is the crucial juncture at which the appeal to common principles may be translated into concerted action, and hence to political power, Tashjian, supra, at 216, 107 S.Ct. 544. California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567, 568, 120 S. Ct. 2402, 2404, 147 L. Ed. 2d 502 (2000).

Ballot Options

One Ballot per Party

Because partisan primaries are conducted for the purpose of selecting individual party nominees, most partisan primaries are administered with separate ballots for each party. A voter’s ability to select a party’s ballot is determined by their party affiliation and/or a particular party’s willingness to allow non-members to participate.

Blanket (Open Partisan) Primaries

Blanket primaries are necessarily open, because all candidates are listed on the same ballot and that same ballot is given to every voter, regardless of party. Therefore, parties have no way to limit access to their own members.

In 1996, California voters approved Proposition 198, which changed California’s closed primary, where only political party members can vote in a given party’s primary, to an open blanket primary.

Proposition 198 changed the State's partisan primary from a closed primary, in which only a political party's members can vote on its nominees, to a blanket primary, in which each voter's ballot lists every candidate regardless of party affiliation and allows the voter to choose freely among them. The candidate of each party who wins the most votes is that party's nominee for the general election.

The Supreme Court held this type of primary system unconstitutional because “California's blanket primary violates a political party's First Amendment right of association.” Democratic Party v. Jones.

The First Amendment protects the freedom to join together to further common political beliefs, id., at 214–215, 107 S.Ct. 544, which presupposes the freedom to identify those who constitute the association, and to limit the association to those people. citing Democratic Party of United States v. Wisconsin ex rel. La Follette, 450 U.S. 107, 122, 101 S.Ct. 1010, 67 L.Ed.2d 82. California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567, 120 S. Ct. 2402, 2404, 147 L. Ed. 2d 502 (2000)

Blanket (Open Non-partisan) Primaries

Because nonpartisan primaries avoid party 1st Amendment concerns, the Supreme Court has upheld the Constitutionality of nonpartisan blanket primaries.

For example, in California, the top-two nonpartisan primary election law never refers to candidates as nominees of any party, nor does it treat them as such. To the contrary, the election regulations specifically provide that the primary “does not serve to determine the nominees of a political party but serves to winnow the number of candidates to a final list of two for the general election.” App. 606, Wash. Admin. Code § 434–262–012.

The top two candidates from the primary election proceed to the general election regardless of their party preferences. Whether parties nominate their own candidates outside the state-run primary is simply irrelevant. In fact, parties may now nominate candidates by whatever mechanism they choose. Washington State Grange v. Washington State Republican Party, 552 U.S. 442, 453, 128 S. Ct. 1184, 1192, 170 L. Ed. 2d 151 (2008)

Most Recently, the California Superior Court validated the Constitutionality of its new Top-Two system.

Here, in contrast to Perry v. Brown (9th Cir. 2012) 671 F.3d 1052, the challenged law does not on its face or in its application “target” one group or another for disparate treatment. Instead, it allows broad access to candidates identifying with any party (or no party) to participate in the primary election and then permits the top-two. Field v. Bowen, CA Sup. Ct. decided Sept. 20, 2013.

Summary

Historically, states have established election systems designed around the partisan purpose of selecting party nominees. Because political parties are private organizations, such systems also confer parties a state-granted right of private association.

This private right of association has come in conflict with an individual’s fundamental right to participate in the electoral process, requiring the state to balance the relative interests.

Recently, states like Washington and California have enacted electoral systems that are conducted for a nonpartisan purpose. Party 1st Amendment concerns do not arise under these systems, and as a result, avoid the need for a balancing test altogether.

Photo Credit: Svanblar / Shutterstock.com