Defining The Center: Most Americans Are More Extreme Than You Think

Given the intense nature of partisanship and polarization, it is tempting to conjure up an image of the electorate in which a majority of common-sense, moderate voters are trapped between two political parties that represent the extremes of American public opinion.

This impression seems to be ratified by a recent poll that shows 38 percent of voters self-identify as "moderates," compared to 33 percent for "conservatives" and 26 percent for "liberals."

Since this 38 percent figure is close to the nearly 40 percent of Americans who consider themselves independents, it is tempting to equate the two: independents are moderates who do not feel at home in either of these extreme parties.

However, this equation confuses an important difference, one between ideological orientation and partisan identification. The former refers to the values, beliefs, and opinions that comprise a person's political worldview, whereas the latter represents how a person chooses to express (or not express) that worldview through partisan affiliation.

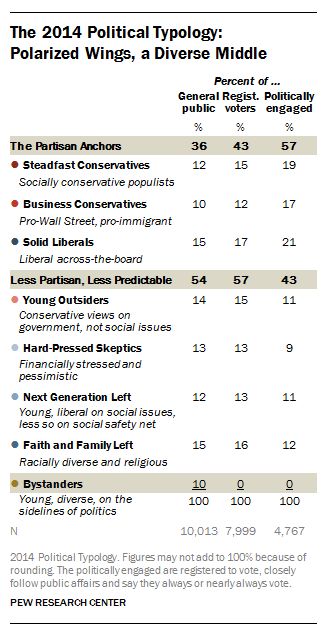

A Pew report from 2014 took a closer look at the true nature of public opinion in the United States and developed a more sophisticated typology – one that goes beyond the simplistic classifications of "liberal," "conservative," and "moderate." After analyzing the results of a 23-question survey, it divided Americans into eight categories based on clusters of common values and beliefs:

While Pew did find that a minority of reliably partisan groups dominate the political process (Solid Liberals for Democrats; Business Conservatives and Steadfast Conservatives for Republicans), it found that the less politically active are not simply frustrated, politically disengaged moderates. Here is the report's conclusion:

[M]ost Americans do not view politics through uniformly liberal or conservative lenses, and more tend to stand apart from partisan antipathy than engage in it. But the typology shows that the center is hardly unified. Rather, it is a combination of groups, each with their own mix of political values, often held just as strongly as those on the left and the right, but just not organized in consistently liberal or conservative terms. Taken together, this “center” looks like it is halfway between the partisan wings. But when disaggregated, it becomes clear that there are many distinct voices in the center, often with as little in common with each other as with those who are on the left and the right.

That our simplistic ideological labels ("liberal," "conservative," "moderate") dissolve under closer scrutiny is hardly surprising. It is not that Americans are inconsistent in their views and stubbornly defy valid, time-tested labels: rather, it is that our labels are too few and broad and are inconsistent with the plurality of Americans' ideological worldviews.

Take, for instance, the issue of gay marriage. While one might expect that gay marriage would have minimal support given the relatively small percentage of self-described liberals in the U.S., a recent poll finds that 61 percent are in favor of it – twice the number of confessed "social liberals."

Yet, considering the ideological make-up of the nonpartisans groups, it makes sense that the figure is as high as it is, especially given the views of the Young Outsiders and the Next Generation Left, which are more liberal on social matters.

These findings, which impugn the validity of the traditional one-dimensional political spectrum ("left-right-center"), also challenge the conventional wisdom regarding the relationship – ideal and perceived – between voter and representative.According to democratic theory, a politician is supposed to represent the average or typical voter in his or her constituency. The so-called "median voter theorem" supposedly guarantees that this is so, since to stray too far from the general will of the constituency ought to amount to political suicide.

As Tyler Cowen describes it in the New York Times, "there is a dynamic that pushes politicians to embrace the preferences of the typical or “median” voter, who sits squarely in the middle of public opinion. A significant move to either the left or the right would open the door for a rival to take a more moderate stance, win the next election and change the agenda."

The theorem aggregates or sums up each voter's views – averages them out – and then imposes a single label on that voter based on that average, but, as we shall see, these labels distort the very views they are intended to summarize, which leads us to question the theorem's accuracy.

Political scientist David Broockman asks us to imagine, for instance, that our "crazy uncle" holds extremely liberal economic views and extremely conservative social views. On an issue-by-issue basis, this voter is extreme, but on average, his views could be said to balance out and be classified as moderate.

Broockman finds that when voters' views are averaged out in this way, politicians appear to hold more extreme views than the public. However, when he breaks down voters' views on an issue-by-issue basis, he finds that the public holds views more extreme than those of elected officials. He writes:

For example, about 40 percent of Americans seem to have more liberal positions on tax policies than most Democratic elected officials, while much of the public would also prefer more conservative policies on immigration and abortion than most Republican elected officials would endorse.

Broockman's scholarship seriously challenges the soundness of the mean voter theorem – but with an unexpected twist. While our elected officials do indeed fail to adequately represent their constituents (as many frustrated independents rightly attest), his work contradicts the idea that our political system has been hijacked by partisan extremists.

He writes that "the metaphor of extreme elites spurning a moderate public is understandably appealing," but nevertheless concludes: "In fact, the Americans who we often call moderates may beless likely to adopt moderate positions on any given issue. These Americans appear more aptly described as “conflicted,” agreeing with each party on some issues and more extreme than either party on others."

These findings call for a new conception of political discourse. While convenient, the traditional political labels and their analogues on the linear political spectrum ("left-right-center") do not adequately express the true nature and diversity of public opinion.

They also have electoral and political implications. If the median voter theorem is a myth (imagine a district full of allegedly moderate "crazy uncles" being represented by a centrist politician), then so is the foundation of our winner-take-all, single-member district (SMD) political system, according to which a single politician is expected to effectively represent the will of his or her constituents.

Given the gross misrepresentation of the electorate in Congress, the diversity of public opinion – in all its breadth – cries out for fuller representation. There needs to be electoral reform that gives a voice not only to moderates, but to citizens of all ideological persuasions, though how that can be achieved is for voters – partisans and independents of all stripes – to decide.