America’s Take: The State of the Union Is NOT Strong

Tuesday, January 29, was supposed to be the airing of the State of the Union Address. However, after a 35-day shutdown, the president's yearly speech has been pushed to February 5.

This change has not affected many, and while the president will likely focus on the economy to make the case that the state of the union is strong, Gallup has found that most Americans don't agree.

Gallup released the results of a survey in January that found that only 28% of Americans were satisfied with the way things were going in the US. Nearly three-fourths of Americans were dissatisfied.

This sentiment hasn't changed much over the last year. In 2018, satisfaction with the state of things in the US averaged at 33%, highlighting a lingering discontent with the political status quo in Washington.

"A dysfunctional government remains, month after month, Americans' pick as the number one problem facing the nation. Obviously, the people taken as a whole want change in Washington," writes Frank Newport.

Most Americans are not happy with the president or Congress, either. Gallup found Trump's approval mid-shutdown to be at 37% while Congress hovers around 20% approval.

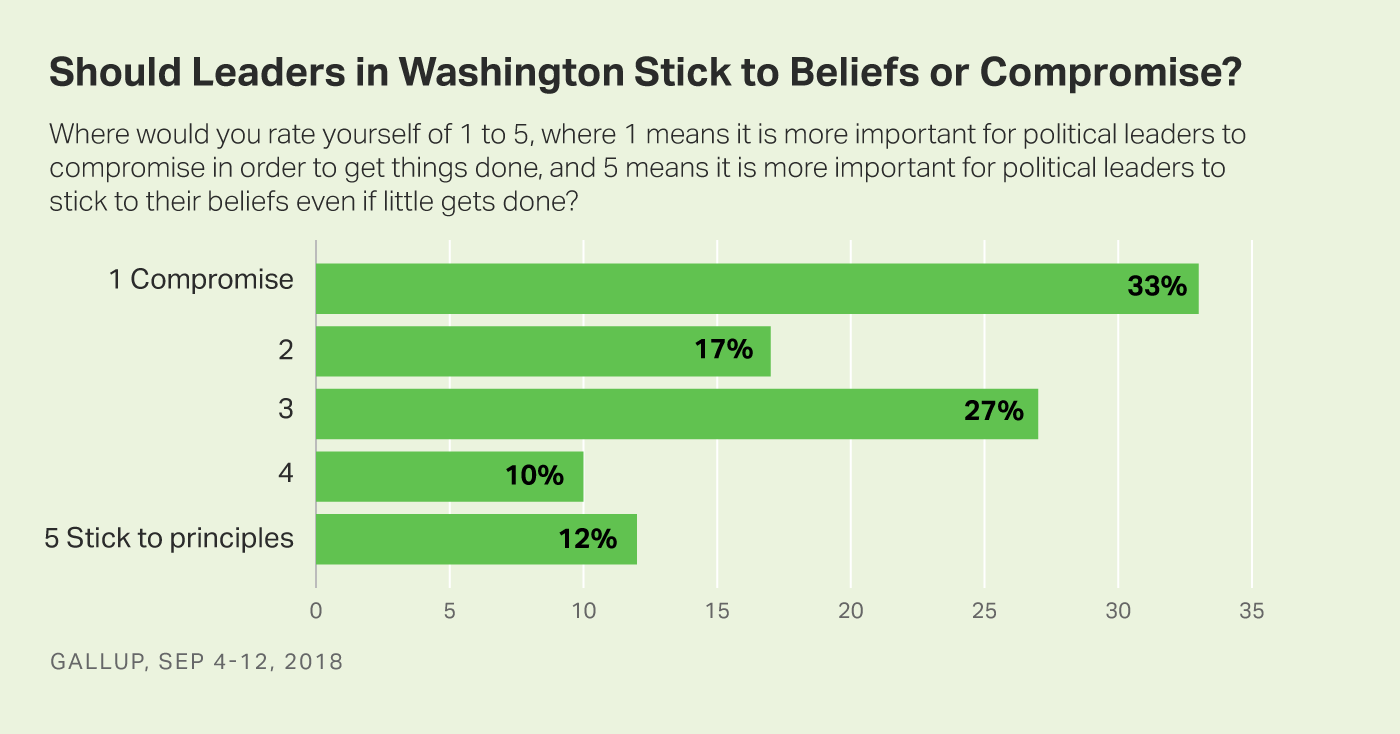

Voters want elected officials to put ideological differences aside and work together -- to compromise rather than rigidly stick to ideological principles.

But the compromise they seek goes beyond simply meeting in the middle. We have seen that type of bipartisanship. It is how we get continuing resolutions that put the US government in another shutdown risk every few months. It is how we get bills that do little or nothing to address the fundamental problems behind the nation's biggest issues.

At the end of the day, "bipartisanship" has meant the bare minimum of what both sides are willing to cede to the other side, and most issues just get kicked a little further down the road.

Why then do members of Congress not compromise if that is what people want? And why do people not vote these members out?

There are a number of variables that go into this question, but at the heart of the issue is how these policymakers are elected. Most members of Congress are first selected in low-turnout partisan primaries -- the most critical stage of the election process in many cases because the district is safe for the party in power.

In other words, elected officials know they have a lot more to be concerned about from primary voters than the voters who show up in November, even though voter participation in the general election is far greater.

Yet because primaries typically bring out the most hardline of the party faithful, or in some cases exclude people registered outside the parties, this voting base continues to shrink and the more it shrinks, the more ideologically pure it becomes.

Many of these voters, though they represent a minority, do not want compromise. They want uncompromising ideological purity from their candidates. So, even politicians who may have once been open to working with the other side are more concerned with being primaried out than the effect long-term gridlock has on the nation.

This is certainly not the only problem with elections -- from ballot access laws, to campaign finance regulations and debate rules, to an inadequate voting method and partisan gerrymandering, etc.

However, it does show that in order for Americans to believe that the state of the union is, indeed, strong we first need broad systemic reform to give the people a political system that puts their interests and needs first.

Photo Credit: Bliss Hunter Images / shutterstock.com

Shawn Griffiths

Shawn Griffiths