No Labels' Failed Presidential Math and Why It Should Focus Its Efforts on Reforming the System Instead

Editor's Note: This piece originally published on Dan Sally's website, Middleweight Politics, and has been republished on IVN with permission from the author. Photo Credit: David Everett Stickler / Unsplash

Earlier this month, No Labels officially ended its plans to field a bipartisan “Unity Ticket” in the 2024 presidential election. While most campaigns end due to a lack of voter support or funding, No Labels’s campaign suffered the unique problem of lacking a candidate.

In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, No Labels Co-Chair Nancy Jacobson cited how “no one wanted the hellish job we were offering.”

In many ways, it doesn’t seem as if the timing could be any better for No Labels. One recent poll showed only 3 in 10 Americans felt a Trump-Biden rematch was good for the country, a mirror image of earlier polls showing 70% of Americans didn’t want to see either candidate on the ballot in 2024.

Polling by Gallup shows the number of Americans who feel a third major party is needed is at an all-time high and the number of Americans identifying as independent is almost double the number of people who identify as either Republican or Democrat.

At the same time, there’s no shortage of political exiles to choose from. Mitt Romney, Liz Cheney, Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and Nikki Haley have all found themselves shunned by their party and have all expressed concern for the “torches and pitchforks” approach to governing that has become all the rage today.

So, with this vast ocean of disaffected independents to choose from, why didn’t one of these savvy political operatives seize the chance to disrupt the system and restore order to Washington?

Because these savvy political operatives know that chance, if it exists at all, is infinitesimally small.

While No Labels’ mission to “elevate extraordinary leaders who put country over party” fills a much-needed void in today’s political landscape, the math behind their third-party bid was flawed, and their efforts would be better spent changing that math.

There’s more than one type of independent voter

Tolstoy wrote, "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

The same could be said for political independents.

Independents are united in their general disdain for both major parties. Research by Pew shows political independents are more likely to view both parties unfavorably and have a higher level of dissatisfaction with the party system itself.

Why they’re unhappy is another story entirely.

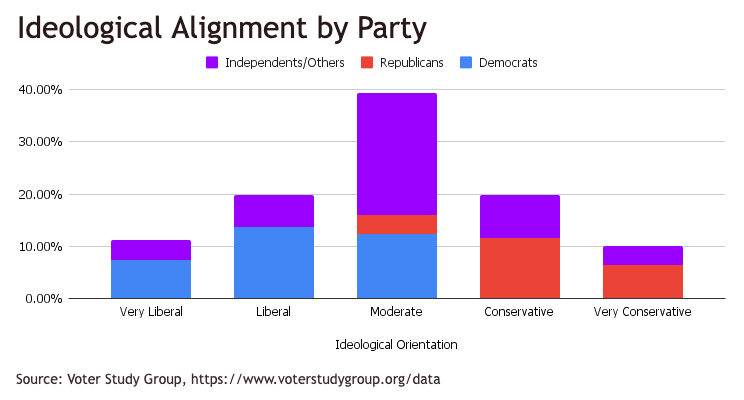

The most recent voter survey by the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group revealed that, while independents were the largest group, about half of them - about 23% of respondents in total - identified as politically moderate.

The remainder either identified as liberal or conservative, meaning that while some independents are unhappy both parties have become too extreme others are unhappy the parties aren’t extreme enough.

Independents also comprised 60% of moderate voters - the remainder being Democrats or Republicans.

This would indicate that, while the number of voters who identify as either moderate or independent is larger than those who identify as more partisan, the number of voters who are truly up for grabs by a centrist third-party ticket is under a quarter of all voters.

Those who align as more conservative or more liberal would be expected to vote for the major party they align with the most, or a minor party candidate with more hardline views. While some moderate Democrats and Republicans might throw their support behind a centrist ticket, No Labels would need to win over 60% of them to be competitive in the popular vote - and those numbers don’t account for how the Electoral College might influence the outcome.

Rule by majority, or by default?

The second problem is the electoral math of US elections breaks down once more than two candidates enter the race. America’s first-past-the-post system of elections means the winner is the person with the most votes which, in a three-person race, means the threshold for victory could be as low as 33% +1 vote. That math only gets worse as you add candidates.

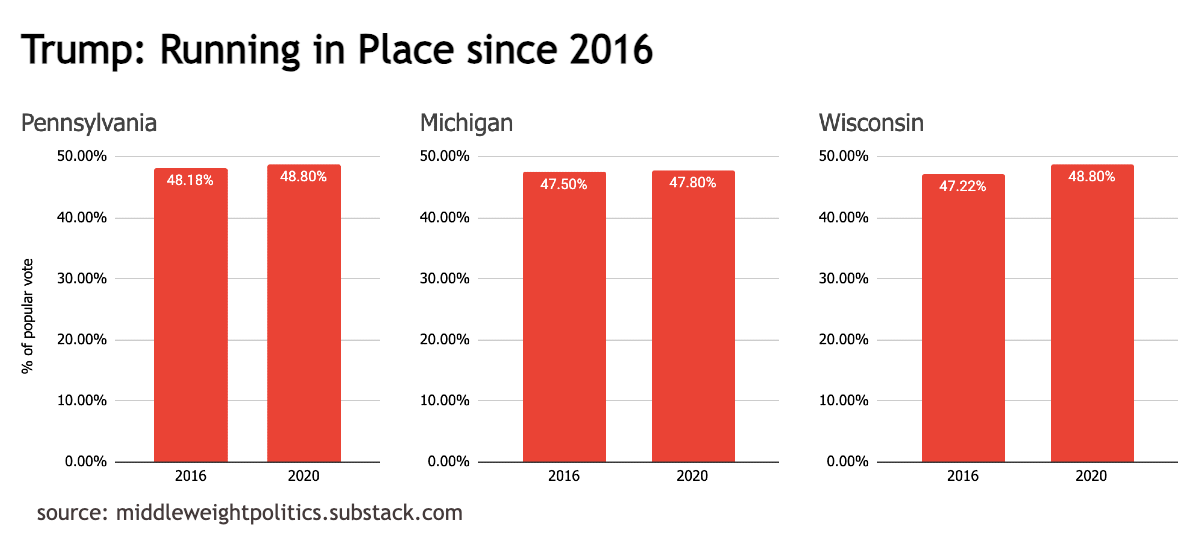

Trump’s 2016 victory is a case study of this principle. Many were shocked that Trump managed to win the traditionally blue states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. People seemed less curious that he lost those three states in 2020 with almost the same share of the popular vote he won in the prior election.

The key difference in all three states was the share of votes that went to minor party candidates in both years, which were around 3.5X more in 2016 than in 2020.

Both campaigns appear to be keenly aware of this, with Democrats attempting to win over undecided voters by assembling an army of lawyers to challenge the ballot access of minor party candidates and actively campaigning against RFK Jr. The Trump campaign has been doing the exact opposite by campaigning to elevate the presence of independent and minor party candidates while also trying to depress turnout amongst Biden voters by highlighting concerns among liberal voters over the administration's approach to climate change and the war in Gaza.

Effectively, both parties have acknowledged that the election is Biden’s to lose, provided there’s no other choice but Trump.

Making Room for More Choices

What No Labels failed to acknowledge in its push for a more moderate choice in the 2024 election is that their chances of winning the White House without a candidate on the ballot are just about as good as if they’d managed to find someone to run. History shows moderate Democrats and Republicans are too afraid of vote-splitting to defect in large enough numbers to give a third-party candidate the plurality of the vote needed to win.

A better option would be to put their energy and funding behind promoting reforms that would change the math of presidential elections so the support of a true majority of voters would be required to win.

Ranked-choice voting, a method of elections where voters rank their candidates in order of preference, is the best option. This would allow voters who prefer an independent or minor party candidate to cast their ballot for the person they like the most, and still throw their support behind the major party candidate they prefer if their first choice doesn’t win.

While its use in federal elections is limited, elections in Maine and Alaska have shown it to favor more moderate, consensus-minded candidates. Senators Susan Collins (ME) and Lisa Murkowski (AK) were two of seven Senate Republicans who voted to convict Donald Trump after the January 6th attack, and Representatives Mary Peltola (AK) and Jared Golden (ME) lead the Blue Dog Coalition - a group of conservative Democrats who advocate for “bipartisan consensus rather than conflict with Republicans."

Sound familiar?

No Labels is correct in that a large number of voters would prefer a more moderate candidate who could bridge the partisan divide and get government back into the business of governing. The key is changing our system of elections so that preference actually matters.